AI4Math

Sections

AI for math

I am interested in AI for math for three reasons.

First, AI pushes the boundary of pure mathematics. AI can help mathematics in many different ways.

- Research: for example, our paper at the ICML 2025 AI4Math Workshop. Many open problems come with verified datasets; from these, machine learning methods can extract useful patterns. This can refine existing conjectures and give mathematicians promising directions to pursue.

- Assistance: LLMs can help researchers in day-to-day work. Modern LLMs are trained on a huge amount of material across many subjects and are good at gathering and synthesizing information. Often, when we ask an LLM, it can suggest references and even draft arguments based on what it has seen. Nowadays, the amount of information is growing rapidly and even experts cannot keep up with all progress; LLMs can help with this.

- Automation: AI may eventually generate new mathematics. With the help of Lean, LLMs can even produce machine-checkable arguments. Several start-ups have trained their own models and claim to prove striking results (for example, axiom, harmonic). Although I do not believe LLMs can truly “think” like mathematicians, I do believe they can recombine the material they were trained on and produce arguments that may help us solve open problems.

Second, AI reshapes mathematics education. From my experiments, pre-trained LLMs (like ChatGPT) are already capable of passing graduate-level qualifying exams: much of this “bookkeeping” knowledge is effectively stored in the model parameters. Personally, I use LLMs to learn new areas (for example, hyperbolic geometry) and to generate clear HTML and GIF visualizations to help explain my research. Everyone has access to LLMs, and how they are used will divide outcomes: top students use them to accelerate learning, while others may simply hand homework to an LLM and hope it finishes it. We cannot ban LLMs from university education, so we need to learn how to live with them. Currently, I am developing AI agents specialized for math education, and I believe they will reshape how we teach and learn mathematics.

Third, AI may help secure real-world systems. In industries where correctness and maintainability matter—for example, self-driving cars and quant finance—bugs are extremely costly. Systems are often small but critical, and long-term maintenance is expected. Standard testing (which checks logic against a limited set of test cases) is not always enough. In these settings, formal verification is crucial: it aims to prove that the system’s logic is correct, greatly reducing the risk of corner cases. As far as I know, self-driving systems already have concrete needs for formal verification.

Formal verification is closely related to mathematical proof, using languages such as Lean, so it depends heavily on mathematical ability. With the help of AI, we may be able to build new automation for formal verification. Companies like Galois have taken steps in this direction. I am particularly interested in the Coq and OCaml stack. If you are also interested, feel free to contact me.

Machine Learning for Predicting $\mathbb{Q}$-Gonality of Modular Curves ICML 2025, AI4Math Workshop

In this work, we study the $\mathbb{Q}$-gonality of modular curves. For a congruence subgroup $\Gamma\subset\mathrm{SL}(2,\mathbb{Z})$, the associated modular curve is $X_\Gamma=\mathbb{H}/\Gamma$; when the action is free, this is a hyperbolic Riemann surface. The $\mathbb{Q}$-gonality of $X_\Gamma$ is the minimal degree of a nonconstant rational map $X_\Gamma\to\mathbb{P}^1$ defined over $\mathbb{Q}$. Computing $\mathbb{Q}$-gonalities is notoriously difficult.

Conjecture The $\mathbb{Q}$-gonality of $X_\Gamma$ can be determined (uniquely) from a finite collection of arithmetic and geometric invariants: genus, number of cusps, Mordell–Weil rank, log-conductor, level, number of rational cusps, coarse class number, and coarse level.

While the conjecture remains open, we develop numerical evidence and a refined theoretical conjecture. One reason numerical methods can work well here is that mathematicians have built high-quality datasets for existing modular curves, notably the L-functions and Modular Forms Database (LMFDB). It contains cases where the $\mathbb{Q}$-gonality is known and cases where the $\mathbb{Q}$-gonality is only bounded theoretically. Notably, this mathematical dataset is noise-free.

This makes it natural to apply regression techniques. We tested classical machine learning regression models such as XGBoost, FNN, and FT-Transformer, achieving around $90\%$ accuracy. For example, FT-Transformer:

| Dataset | Accuracy | $R^2$ | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| $D_{train}^{i}$ | $95.62 \pm 0.70$ | $0.9389 \pm 0.0325$ | $2.813 \pm 0.972$ |

| $D_{val}^{i}$ | $93.17 \pm 0.58$ | $0.9971 \pm 0.1079$ | $3.770 \pm 4.001$ |

| $D_{test}$ | $93.64 \pm 0.63$ | $0.9968 \pm 0.0007$ | $0.496 \pm 0.055$ |

| $D_{bounds}$ | $93.46 \pm 0.82$ | – | – |

Table: Performance metrics for the FT-Transformer model across different datasets

It is not surprising that the results are good. The drawback is also clear: these methods are “black-box” models, meaning they yield an overly complicated (often overfit) formula while the true relationship remains unknown. Their generalization can also be limited. As a result, mathematicians cannot easily use these models to formulate a reasonable conjecture, so they do not directly lead to a proof.

Recovering the true relationship and finding an explicit formula is often called symbolic regression. A classical approach uses genetic algorithms, where each generation mutates expressions and filters out the least-fit candidates. In our task, we care not only about standard regression metrics like MSE and $R^2$, but also whether the prediction hits the exact target (accuracy). This makes the problem much harder.

For genetic-style algorithms like PySR, the environment can be too “cruel” for the “species”: no strong-enough offspring survives, even if we guide evolution toward lower MSE. In the era of LLMs, researchers have developed LLMSR, which feeds information to an LLM and asks it to propose the relationship directly. This can work for extremely simple tasks (e.g., Newtonian motion) if the relevant formulas are well represented in training data. They also built a benchmark and report good performance. But for slightly more complicated open problems, LLMs often produce over-simplified formulas that perform poorly.

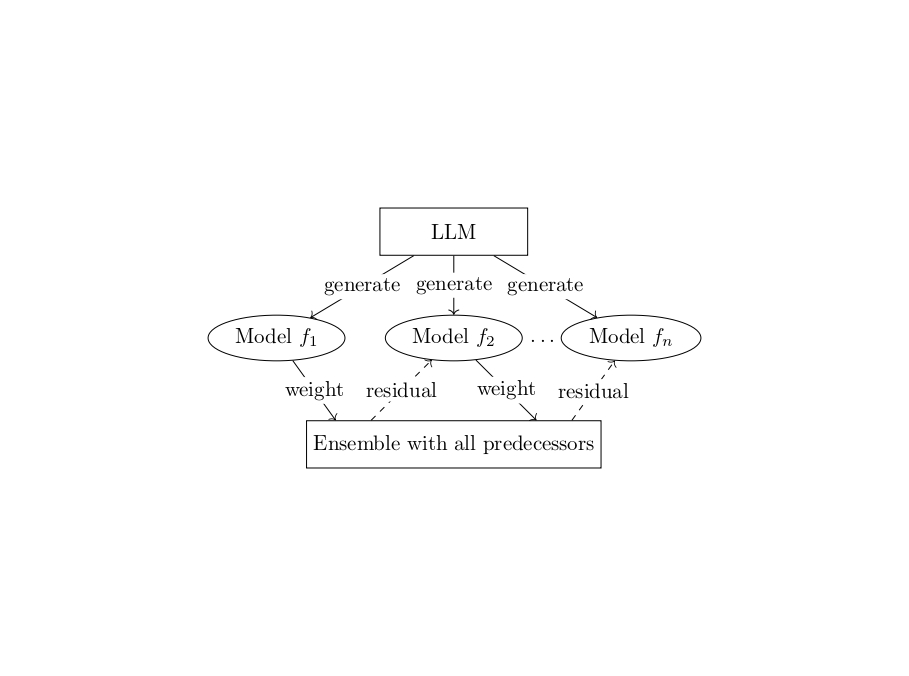

To address this, we introduce LLM-Boost, a hybrid method that combines large language model (LLM)-based feature generation with AdaBoost.

Details (you may skip this): To recover an interpretable symbolic expression, we assume the true functional relationship can be approximated by an additive model of the form

\[\tilde{f}(x) = \sum_{i=1}^k w_i f_i(x),\]where each $f_i$ is a simple, non-linear feature function. These candidate features are generated by a pre-trained language model $\pi_\theta$, conditioned on dynamically updated prompts $p_i$, i.e., $f_i = \pi_\theta(\cdot \mid p_i)$. The prompts are adaptively modified to ensure no duplicate features are produced. To construct the ensemble of features, we adopt a boosting-inspired approach similar to AdaBoost. At each iteration $k$, we compute the residual of the current model,

\[\widetilde{f}_k = \sum_{i=1}^k w_i f_i\]and query the LLM to generate additional candidate features. These features are stored in a memory buffer. We then fit the residual using each feature in the buffer and select the one that yields the greatest improvement in predictive accuracy. This selected feature is incorporated into the model, and the process is repeated.

This process is equivalent to linear regression on selected features via the Frisch–Waugh–Lovell theorem when the initial factor model is linear regression. However, this viewpoint allows us to generalize further. Unlike standard regression models optimized purely for mean squared error, our final model prioritizes interpretability and accuracy, often resulting in lower bias and more meaningful symbolic expressions. The greedy selection strategy balances the exploitation of promising features with the exploration of novel ones, enabling efficient and interpretable symbolic discovery.

Key takeaways:

- LLMs are not omnipotent; you have to let them evolve, starting from very simple tasks (similar to AlphaEvolve).

- Orthogonalization makes each step “meaningful”: we can explore new directions in the solution space at every iteration.

- Treat the LLM as a “guesser”: record what it gets right and iterate.

LLM-Boost attains state-of-the-art performance among symbolic-regression approaches for this problem, and achieves the highest percentage of test cases that fall within the theoretical bounds—improving on prior interpretable methods and matching the accuracy of black-box machine-learning baselines.

| Dataset | Accuracy | $R^2$ | RMSE |

|---|---|---|---|

| $D_{train}$ | 73.49% | 0.9973 | 0.5913 |

| $D_{val}$ | 72.91% | 0.9945 | 0.6718 |

| $D_{test}$ | 73.50% | 0.9895 | 1.9814 |

| $D_{bounds}$ | 81.52% | – | – |

Table: Performance metrics for the LLM-Boost model across different datasets

In particular, our final formula is extremely simple:

\[\begin{aligned} \text{Q-gonality} \; &=\; 0.113 \times \text{genus} \\ &-\; 0.347 \times \log(\text{level}+1) \\ &-\; 0.760 \times \bigl(\text{rational cusps} / (1 + \text{genus})\bigr) \\ &+\; 0.202 \times \exp(-\text{rank}) \\ &+\; 0.027 \times \text{log conductor} \\ &+\; 0.011 \times \bigl(\text{cusps} / (1 + \text{rank})\bigr) \\ &-\; 0.026 \times \sqrt{\text{coarse class num} + 1} \\ &+\; 0.003 \times \text{coarse level} \\ &+\; 2.834 \end{aligned}\]We believe that LLM-Boost can be applied to many other fields, e.g., $\alpha$-mining and factor model optimization in quant finance.